L'appendice Operandi

Posted on February 20, 2014 by VINGT EditorialWords: Jill Diane Pope

Images: Sati Leonne Faulks

In 1754, Harold Walpole coined the term serendipity to describe the “accidental sagacity” for which he had developed a reputation. In 2014, as I sat down with artists Valeriano Ortiz and Edgar Sarin in their home and atelier to discuss their new initiative, art groupuscule appendice Operandi, I considered how so much of life – whether business or pleasure – is about being at the right place at the right time. Ortiz and Sarin certainly have this knack. Part of the new vanguard of French artists, they have taken on the challenge of reinventing the art world to meet the needs of their generation and beyond. Drawing on their engineering backgrounds, young blood and no small amount of nous they have started their odyssey at the place many would regard as being at the centre of it all – Paris.

This was the second time I had been to their studio, yet I had forgotten the way there, and had to listen for the strains of music that I knew would be emanating from the apartment to make sure I had the right floor. I wasn’t surprised by my disorientation: when you are with Ortiz and Sarin time seems to stand still – a feeling that begins from the moment you turn onto the quaint, tiny impasse in the ninth arrondissement where their building is located. As you enter the apartment the sensation is amplified. There is a remarkable quality to the space, although it is difficult to identify exactly what. Seemingly independent of the weather outside, the apartment always seems drenched in light. At first glance the interior seems furnished in accordance with an elegant, if not typical, Parisian sensibility with antique furniture, indoor plants and a neutral colour palette, until you realise this is but a canvas onto which is superimposed a carefully curated collection of objects. These objects, equal measures aesthetic and functional, offer a glimpse into the personalities who placed them.

Background: ‘http://www.google.fr/search?q=epicure&secure=off’, [email protected], 2013

A cane swings nonchalantly from a curtain rung. A boater hat is poised on a hook. A skateboard leans defiantly against a cabinet. A wall-mounted clipboard grips a sheaf of brown paper scrawled with mathematics formulae. Even the upright piano is most certainly not just ornamental. In fact the first time I had been chez appendice Operandi was for a Sunday morning piano recital – a duet by Ortiz and Sarin, accompanied by a selection of vegetables.

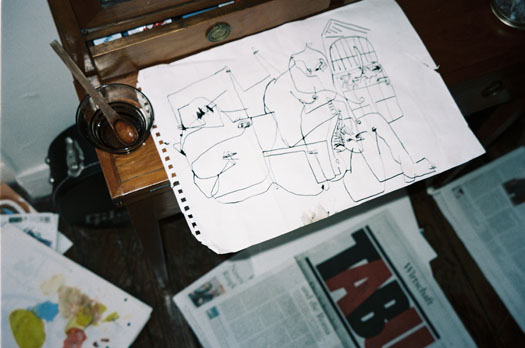

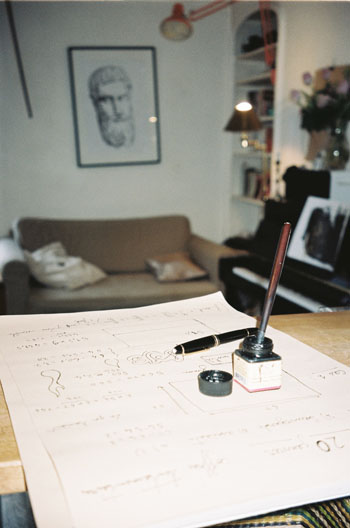

As they move around the apartment, exchanging the bottles of Indian ink, pens and drawing papers that had covered the large, wooden table for a silver tray laden with a kettle, glasses, spoons and honey, their bodies work in concert and contrast. Although at times they appear effortlessly synchronised and share the same incandescent energy, Ortiz and Sarin are as different as they are similar. Once we were seated at the table, tea poured, without hesitation Sarin launched into describing the Operandi: “it’s not an enterprise but an adventure, an organic structure giving new breath to the French art scene”, Ortiz added “it’s a new way to broadcast art pieces, of thinking and finding a way to fit with our generation”. These deceptively simple statements belie the lofty ambitions of their project – a new “vertically integrated” system for artistic distribution that presents an alternative to the traditional commercial gallery model. Their generation – that which straddles the pre and post internet age – provides the perfect launching point for syncretising the forgotten ideal of an artistic community, with the issues and challenges faced in an increasingly global and connected world.

This new system revolves around a model of “peer-to-peer” hebergement or lodging, where the works of the artists represented by the Operandi (including Ortiz and Sarin themselves) are accommodated by hosts for short or long term arrangements, until they are sold. “Usually if an artist wants to exhibit it takes a lot of time for him to show his art to a lot of people – our system is like “burning steps”, the works of art go directly from creation to putting it in people’s homes” said Ortiz.

This democratic process benefits the artists in the Operandi – none of who are Beaux-Arts trained – as well as affording art lovers who might not have the means to purchase original art pieces the ability to enjoy works in their home. Not only this, Ortiz and Sarin believe that housing art in such intimate environments gives the art the respect it deserves, and allows a qualitative, rather than quantitative connection to be developed.

“We think that if one person lives with the art piece, when he talks about it will be transmitted through human sensitivity, out of texture, sensation, sense of smell, whatever. That is more qualitative than if one hundred thousand people saw it on their screen while they were eating Miel Pops. That’s why we don’t use internet networks so much” said Sarin.

The Operandi was borne out of its founders’ disenchantment with the current Parisian art scene. After moving to Paris in 2013 they found no resonance with the art circles or traditional gallery model, which they feel has irrevocably lurched towards a commercial imperative. Ortiz and Sarin view the current proliferation of “white cube galleries” as outdated and restrictive – they prevent any meaningful, sensory connection with art from being established. They find the stale atmosphere that surrounds them, as well as logistical constraints such as limited opening hours and the fleeting contact gallery visitors have with each work, as anathema to how art can and should be experienced. The Operandi aims to re-insert that lost pathos, humanity and sensuality into art. “What we aim to do is put life back into something that has become mostly business” said Sarin.

This emphasis on human experience is a part of everything they do – appendice Operandi sees part of its manifesto as a global project concerned with “re-establishing fluent human relationships”, which have been lost through the increasing reliance on easier, but ultimately less fulfilling, digital interactions. Wherever possible they conduct their business in the physical rather than digital realm, shunning the quick fix of social media; even the artists selected by appendice Operandi work only in non-digital media. Ortiz described this process as “rehabilitating humans to their most natural process”, while Sarin confessed his biggest fear is “that we are losing the ability to live together, the ability of the human being”. They also host a range of provocative events from their extraordinary opening exhibitions, to music performances, lunches and salons where they, as well as their friends and contacts, can expand their networks. A recent opening lay somewhere between spectacle and exhibition; guests mingled with performance artists, and were left to interact with a range of props from a typewriter, red wine served in test tubes, garlic and toothbrushes.

Rather than simply demonising technology, Ortiz and Sarin are quick to acknowledge its importance. Hailing from technology-focused backgrounds (they both trained as engineers in the fields of energy, systems and organisation) they claim the internet is their biggest inspiration. The pair recognise their scientific savoir-faire is one reason why they would not be satisfied merely creating art within those existing systems. “We just can’t create and live as artists without creating our way of spreading the art”, Ortiz said, “We have to make the future, because we are the new generation. We cannot use established systems to create the future we want to have”. They view both their disparate pursuits of art and science as quests for truth where the process – the experimentation and accidental discovery – is more important than the end result.

This dichotomy, superficially different but inextricably similar, reflects the chiaroscuro of Ortiz and Sarin’s own relationship – one of the purest platonic partnerships, creatively and personally, I’ve seen. They referred to it as “fusional”, “an amazing thing” and “a genetical system” and it is true since the inception of appendice Operandi in 2013 they have lived in very close quarters, sharing their private and professional lives. This emotional and intellectual communion seems crucial to their creative success, in fact they both agree that the synergy of this somewhat unorthodox arrangement has helped them maintain their motivation and focus. “We have our own personalities, his and mine, but a convergence of ideas of fluidity” said Ortiz. Sarin added that they both know how to execute those ideas – their exchange is more than just cerebral.

Ortiz likened their creative partnership to a negative and positive energy field. Who is negative and who is positive? That’s a question that is easily answered, apparently, as Sarin admitted that much of his art is produced in a state of “morbid excitation” – a place for him to process his angoisse – whereas Ortiz is inspired by each and every aspect of life, to the point where he does not distinguish his creative process from his quotidian reality. Ortiz described this as being “a sponge in an environment. When I’m drawing, I’m distilling life.”

Both are always clothed with distinctive formality; an idiosyncratic style that lies somewhere between vintage and contemporary, rendering both men at once ageless and youthful through its sheer anachronism. Yet Ortiz is more fluid and more present – his face open, expressive and ambivalent towards its three-day growth; his rolled-up sleeves and unruly hair refusing to be curbed. His laughing eyes as much as his attentive concentration betraying his gentle sensitivity as he folds himself up on his chair. Sarin is angular and more restrained, legs crossed, his tall frame impeccably concealed in coat and tie. His hair, tamed with pomade, dark against his clean-shaven countenance. A permanent haze of cigarette smoke, language and gestures constantly obscures him, creating an opacity only occasionally penetrated by a conspiratorial smile.

As the interview continues, sometimes I find myself speaking with only Sarin, or only Ortiz, as one or the other jumps up, distracted by a new idea. Ortiz, spying their neighbour through the window grabs their camera to take pictures (and is promptly disappointed when the neighbour shuts their curtains); Sarin strays over the piano and plays a few bars before coming back to rejoin the discussion. As the afternoon light dimmed, they worked together to fix a light that wouldn’t switch on.

Their art provides further insight into their complementary dynamic. Ortiz’s work clamours with life, chaotic ink lines run over each other, capturing the relentless rhythm of humanity, the black traces sometimes softened by seamless pools of colour. His art pieces use the decisive power of the line to communicate an intense amount of energy through its infinite form.

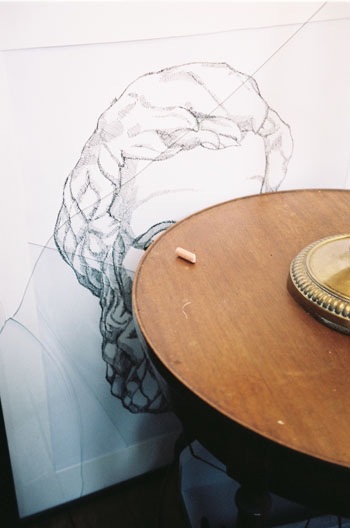

Sarin’s latest work, a series of five pieces inspired by a series of paranoid night terrors where he envisaged his own assassination, are as much a cathartic as an aesthetic exercise. The five works hint at the identity of his killer: objects are painstakingly fastened to the canvases, each of which are painted with a single, precise, geometric shape in a bold, primary colour. Further clues were built into the back of each frame, so that in the case of Sarin’s death, the works could be broken open, leading people to his female assassin.

For Ortiz and Sarin, it is impossible to separate art from life – and it’s clear from the encouraging response that the Operandi has already received from their artists and clients that they speak for others as well. Looking to the future, Sarin predicts the evolution continuing “I am absolutely sure that in five years people will say “he buys art at a gallery” and laugh”. The two artists agree, with characteristic laissez-faire, that when the time is right, their future plans will come to fruition, and in the mean time, it is safe to say that they will leave a real and lasting impression on those whose paths manage to cross with those of appendice Operandi.

‘http://www.google.fr/search?q=aristophane&secure=off’, [email protected], 2013